November 15, 2012

Psychology Matters

Rick Kahler believes that financial planners who do not factor in the psychological aspects of their clients’ money problems are “missing the elephant in the room.”

Kahler, a founding board member for the Financial Therapy Association, usually meets with each new client in the presence of a therapist. And for the minority of his clients who are “stuck” and can’t get past their money issues, which are often rooted in childhood, he asks that they submit to psychological coaching.

In his 2008 book, “Facilitating Financial Health,” Kahler identified several common money disorders. The South Dakota planner recently shared his ever-evolving list, which Squared Away used as the basis for the above slide show.

Click here to watch an interview in which Kahler talks about our “number one stressor.”Learn More

November 13, 2012

Women Don’t Ask

Why do men earn more than women? Attitude!

Last week on Squared Away, Francine Blau, a Cornell University labor economist, discussed the economic and other external reasons behind why women earn less than men. But there’s another way to look at it: women’s behavior differs from men’s – and that plays a role in how much they’re paid.

A woman earns 77 cents for every dollar that a man earns. This disparity undermines women’s well-being, reducing their standard of living and affecting everyone’s retirement – including their husband’s.

The following is an excerpt from a June 2003 article I wrote as a Boston Globe a reporter about an experiment by researcher Lisa Barron, a professor of organizational behavior at the Graduate School of Management at the University of California, Irvine. It involved 38 future MBAs – 21 men and 17 women – who participated in mock job interviews with a fictitious employer.

In the mock interviews, the students were offered $61,000 for a new position. Here’s what I wrote about the differences in men’s and women’s approaches to their pay negotiations:

Men, responding to the salary offer, asked for $68,556, on average, while women requested $67,000 for the same job.

More revealing were differences in fundamental beliefs men and women expressed about themselves when Barron questioned them: 70 percent of the men’s remarks indicated they felt entitled to earn more than others, while 71 percent of women’s remarks showed they felt they should earn the same as everyone else. Also, 85 percent of men’s remarks asserted they knew their worth, while 83 percent of women’s remarks indicated they were unsure. …Learn More

November 8, 2012

Women’s Pay Gap Explained

Lower pay for women came up – where else! – in the foreign policy debate between President Obama and Governor Romney. It affects women’s living standards, single mothers’ ability to care for their children, and everyone’s retirement – husbands and wives.

To understand why women earn 77 cents for every dollar earned by men, Squared Away interviewed Francine Blau of Cornell University, one of the nation’s top authorities on the matter. A new collection of her academic work, “Gender, Inequality, and Wages,” was published in September.

Q: How has the pay gap changed over the years?

Blau: For a very long time, the gender-pay ratio, which is women’s pay divided by men’s pay, was around 60 percent – in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Around the 1980s, female wages started to rise relative to male wages. In 1990, the ratio was 72 percent – that was quite a change, from 60 to 72 in 10 years. We continued to progress but it is less dramatic. In 2000, it was 73 percent. Now it’s 77 percent – that’s the figure that came up in the debate.

Q: Why do women earn less?

Blau: There are two broad sets of factors: the first is human capital and the factors that contribute to productivity and the second is discrimination in the labor market. Women have traditionally been less well qualified than men. The biggest reason here is the experience gap between men and women. Traditionally, women moved in and out of the labor force, and that lowered their wages relative to men.

But when we do elaborate studies – my recent study with Lawrence Kahn in 2006, for example – we find that when we take all those productivity factors into account we can’t fully explain the pay gap. The unexplained portion is fairly substantial and is possibly due to discrimination, though it could be various types of unmeasured factors. So in the 1998 data used in our 2006 article, women were making 20 percent less than men per hour. When we take human capital into account, that figure falls to 19 percent. When we add controls for occupation and industry – men and women tend to be in different occupations and industries – we can get a pay gap of 9 percent. This unexplained gap of 9 percent is potentially due to discrimination in the workplace. …Learn More

November 6, 2012

Dicey Retirement: The Long Ride Down

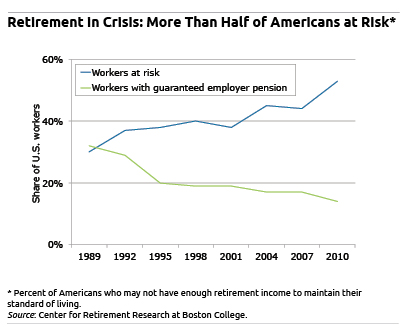

No one really needs confirmation of how tough the Great Recession was. But the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College has quantified the decline – and it’s brutal.

Investment losses and falling home prices placed 53 percent of U.S. households in danger of a decline in their standard of living after they quit working and retire, reports the Center, which funds this blog. That’s up sharply from 45 percent in 2004, prior to the financial boom, which created a strong – albeit fleeting – increase in Americans’ wealth.

The longer-term erosion in Americans’ retirement prospects is even more troubling and reflects deeper issues. The Great Recession just hammered the point home.

In 1989, just under one-third of Americans faced such dicey retirement prospects. The steady erosion since then coincides with the near-extinction of traditional employer pensions that guaranteed retirees a fixed level of income. It turns out that the DIY system that replaced them, a system reliant on Americans’ ability to save in their 401(k)s, is not working.

In 1989, just under one-third of Americans faced such dicey retirement prospects. The steady erosion since then coincides with the near-extinction of traditional employer pensions that guaranteed retirees a fixed level of income. It turns out that the DIY system that replaced them, a system reliant on Americans’ ability to save in their 401(k)s, is not working.

Older baby boomer households with 401(k)s have just $120,000 saved for retirement, according to the Center. That’s not even enough to pay estimated medical costs not covered by Medicare. Retirement savings for all older boomer households is a paltry $42,000 – that means a lot of people have no savings…Learn More

November 1, 2012

Kids to Washington: Keep It Real

Leave it to high school kids to inject some much-needed perspective into our economic and policy debates.

In Tuesday’s election, the presidential election may come down to a few swing states. But the next president, whoever he is, faces tough challenges – topped by the massive destruction of roads and transit systems wreaked by Hurricane Sandy, a tepid economy, and the “fiscal cliff” that a divided Congress enacted to automatically cut the $1 trillion budget deficit.

This video, by students at the East Coweta High School in Sharpsburg, Georgia, was among the winners of a contest sponsored by the Council for Economic Education, a national financial literacy organization that also has state chapters.

Click here for winning videos submitted by high schools in New Jersey and Maryland.Learn More

October 30, 2012

Blame Aid Policies – Not Tuitions

Admissions policies and financial aid packages at individual colleges – not just tuitions and fees – are significant determinants of student loan levels, according to new research.

No wonder there’s a cottage industry of financial planners who specialize in counseling families on college admissions: this granular – and often invisible – information about financial aid is critical to whether your child carries a burdensome debt load with his diploma on graduation day.

The media and policymakers – and (Squared Away adds) parents – “have assumed that tuition and university sticker prices are the primary if not the sole factor driving the rise in student indebtedness,” James Monks, an economist in the University of Richmond’s Robins School of Business, concluded in an October paper. “This assumption ignores the substantial impact that college and university admissions and financial aid policies” have in determining debt levels.

Certainly parents should pay attention to tuition and fees. But Monk found that public college admission policies that are blind to students’ financial circumstances produce students with “a higher average debt upon graduation,” which tends to fall on their lower-income students. When a college says that it is “need-blind,” it is saying that it looks at each student’s financial situation only after deciding whether to admit him or her based on test scores, grades and letters – this policy is typically aimed at increasing enrollment of low-income students. After agreeing to accept a student, the institutions try to help those who need it most through their financial aid packages. But this aid often falls short, requiring heavy borrowing by students.

In contrast, the target of some private institutions is to maximize the number of students graduating with no debt or limited debt. At institutions with such policies, Monks found that students have significantly lower debt levels than institutions that lack this policy.

Danielle Schultz, a straight-talking Evanston, Illinois, financial planner said most public colleges claim to be need-blind in selecting their incoming freshman class. But at a time when state budgets are tight, far fewer now have the financial resources to back up such a policy, she said, which drives up borrowing by their students. As for private colleges, she said they’re also feeling financial pressure and believes that fewer institutions than in the past can afford to maintain generous no-debt policies.

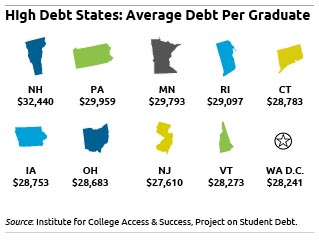

Rising debt levels is the result. U.S. college graduates had $26,600 in student debt last year, up 45 percent from 2004, according to a new report by the Institute for College Access and Success.

Rising debt levels is the result. U.S. college graduates had $26,600 in student debt last year, up 45 percent from 2004, according to a new report by the Institute for College Access and Success.

Schultz, who just successfully shipped her daughter off to college – Bryn Mawr outside Philadelphia – describes college application as a treacherous process rife with pitfalls.

“Schools are in the business of forking over the least money possible to get the most motivated kids and the most diversity,” she said. The onus is increasingly on parents “to think hard about what kind of dollars they are willing to fork over.” These days, it’s about the major: can the student get a job after college? Her rule: don’t borrow more than the student can expect to earn the first year after graduation…Learn More

October 25, 2012

A Dozen Things Women Need to Know

While Squared Away’s goal is to increase everyone’s understanding of how their behavior affects their financial security, substantial attention has been paid to women.

Since going live in May 2011, this blog has posted numerous articles on women’s unique – and often more challenging – financial concerns. Women earn less, live longer, save less for retirement, and are more likely than men to take on the financial burdens associated with caring for children or elderly parents.

Click on “Learn More” for links to a dozen recent articles, from the concerns of young career women to widows. They include “He’s a Rabid Saver; She’s a Spender,” and “Boomer Moms: Take Care of Yourself For Once,” and “You Are Not Alone…”

Learn More