August 15, 2019

Walk? Yes! But Not 10,000 Steps a Day

A few of my friends who’ve recently retired decided to start walking more, sometimes for an hour or more a day.

Becoming sedentary seems to be a danger in retirement, when life can slow down, and medical research has documented the myriad health benefits of physical activity. To enjoy the benefits from walking – weight loss, heart health, more independence in old age, and even a longer life – medical experts and fitness gurus often recommend that people shoot for 10,000 steps per day.

But what’s the point of a goal if it’s unrealistic? A Centers for Disease Control study that gave middle-aged people a pedometer to record their activity found that “the 10,000-step recommendation for daily exercise was considered too difficult to achieve.”

Here’s new information that should take some of the pressure off: walking about half as many steps still has substantial health benefits.

I. Min Lee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston tracked 17,000 older women – average age 72 – to determine whether walking regularly would increase their life spans. It turns out that the women’s death rate declined by 40 percent when they walked just 4,400 steps a day.

Walking more than 4,400 steps is even better – but only up to a point. For every 1,000 additional steps beyond 4,400, the mortality rate declined, but the benefits stopped at around 7,500 steps per day, said the study, published in the May issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

More good news in the study for retirees is that it’s not necessary to walk vigorously to enjoy the health benefits. …Learn More

August 13, 2019

Fewer Contingent Workers Seek SSDI

The vast majority of so-called contingent workers – think Lyft drivers, AirBnB hosts, independent contractors, consultants, and freelancers – have built up the work history necessary to apply for federal disability benefits if they become injured.

The 86 percent coverage rate for contingent workers in their 50s and early 60s is less than the 92 percent for regular workers – but not by much.

Despite their relatively high rates of eligibility, however, older contingent workers are significantly less likely to end up on Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) than similar workers in traditional jobs, according to a new study by the Center for Retirement Research.

This finding is mainly driven by contingent workers’ lower application rates for SSDI. Applications are lower even for people with the physical, cognitive or emotional conditions that the government explicitly lists as SSDI-eligible.

“Even the contingent workers who need SSDI the most are less likely to apply for and be awarded benefits,” the researchers said.

They offer a couple reasons for the lower application rates. One reason might be that contingent workers would get less in their disability checks than workers with traditional jobs receive, because the benefits are based on earnings – and contingent workers earn an average $592 per month less than other workers.

A more compelling explanation is that they simply lack access to the natural avenues for learning about the program’s existence and their potential eligibility: unions, fellow employees, and a traditional employment arrangement. For example, private-sector employers often require people on their payrolls to apply for federal SSDI before receiving the company’s disability coverage. Contingent workers outside of this kind of arrangement are rarely covered by any employee benefits, let alone private disability insurance. …Learn More

August 8, 2019

For Family, Caregiving is a Choice

Francey Jesson’s life took a dramatic turn in 2014 when she lost her job at Santa Fe, New Mexico’s airport after a dispute with the city. In 2015, she relocated to Sarasota, Florida to be close to her family. One day, her mother, who has dementia, started crying over the telephone.

Jesson had always known she would be her mother’s caregiver, and that time had arrived. She and her brother combined resources and bought a house in Sarasota, and Jesson and her mother moved in.

“It wasn’t difficult to decide. What was difficult was everything that came with it,” she said.

One reason for the rocky adjustment was that Jesson, who is single, had been preparing herself mentally to take care of her mother’s physical needs in old age. But Kay Jesson, at 88, is in pretty good health. She requires full-time care because she has cerebral vascular dementia, the roots of which can be traced back to a stroke more than 15 years ago.

She is still able to function and has not lost her social skills. Her muscle memory is also intact, allowing her to chop onions while her daughter cooks dinner. But she forgets to turn off the water in the bathtub, mixes up her pills, can’t remember who her great-grandchildren are, and is unable to distinguish fresh food from rotting food in the refrigerator.

She’s also developed a childlike impatience and constantly interrupts her daughter, who works from home for her brother’s online company. “When she’s hungry, she’s hungry,” Francey Jesson said about her mother.

“Nothing ever stops for me. I can’t sit in a room and not be interrupted,” she said. “Sometimes I just want to watch TV for an hour.”

One way she copes is to approach caregiving with a combination of love and bemusement. She uses “therapeutic fibbing” to protect her mother’s feelings, for example, telling her that a friend who died has moved instead to Kansas so she doesn’t grieve over and over again. Francey Jesson also resorts to humor in a blog she writes about her day-to-day experiences. In one article, “Debating with Dementia,” she recounted a conversation about the best way to repair some bathroom floor tile: …Learn More

August 6, 2019

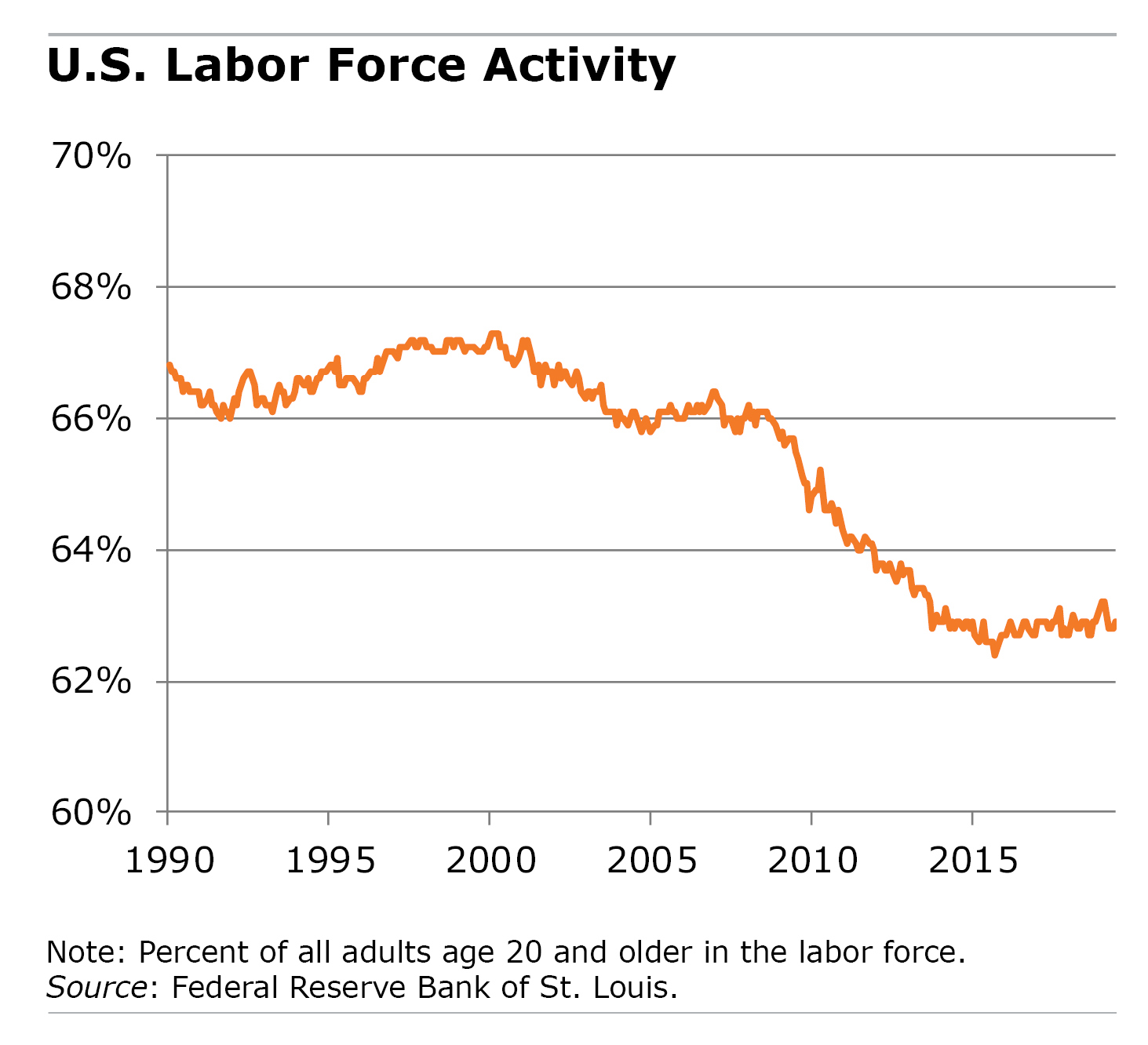

People in their Prime are Working Less

The decline in Americans’ labor force activity started around the year 2000 and accelerated after the 2008-2009 recession. Labor force participation is now at its lowest level since the 1970s.

The decline in Americans’ labor force activity started around the year 2000 and accelerated after the 2008-2009 recession. Labor force participation is now at its lowest level since the 1970s.

The main reason for the drop is our aging population. But the news in a systematic review of current research in this area is a more troubling trend that’s also driving it: people in their prime working years – ages 25 through 54 – are falling out of the labor force.

Prime-age men are the most active members of the labor force. Yet in 2017, only 89.1 percent of them were either working or seeking a job, down from 91.5 percent in 2000, according to the review by University of Southern California economists.

Prime-age women’s labor force activity also fell, to 75.2 percent in 2017 from about 77 percent in 2000. This decline ends decades in which women were streaming into the nation’s workplaces at an increasing rate. One possible reason for the leveling off is the scarcity of family-friendly policies, including more generous childcare assistance.

The forces pushing and pulling various groups in and out of the labor force make it difficult to pin down the primary reasons for the overall drop in participation. The decline among prime-age men and women may be tied to opioid addiction, alcoholism, and suicide. Other studies point to the surge in incarcerations of black men.

And while technological advances like robots and growing trade with China have increased the need for many highly skilled workers, they have reduced the demand for less-educated, lower-paid people, including U.S. factory workers, in their peak working years. The resulting fall in their wages has also made work less attractive to them. …Learn More

August 1, 2019

A Proposal to Fill Your Retirement Gap

David and Debra S. both had successful careers. In analyzing their retirement finances, the couple agreed that he should wait until age 70 to start his Social Security in order to get the largest monthly benefit.

But he wanted to sell his business at age 69 and retire then, so the North Carolina couple used their savings to cover some expenses over the next year.

Waiting until 70 – the latest claiming age under Social Security’s rules – accomplished two things. In addition to ensuring David gets the maximum benefit, waiting guaranteed that Debra, who retired a few years ago, at 62, would receive the maximum survivor benefit if David were to die first.

Other baby boomers might want to consider using this strategy. As this blog frequently reminds readers, each additional year that someone waits to sign up for Social Security adds an average 7 percent to 8 percent to their annual benefit – and these yearly increments spill over into the survivor benefit.

Delaying Social Security is “the best deal in town,” said Steve Sass at the Center for Retirement Research, in a report that proposes baby boomers use the strategy to improve their retirement finances.

Here’s the rationale. Say, an individual wants a larger benefit. Instead of collecting $12,000 a year at age 65, he can wait until 66, which would increase his Social Security income to $12,860 a year, adjusted for inflation, with the increase passed along to his wife after his death (if his benefit is larger than his working wife’s own benefit). The cost of that additional Social Security income is the $12,000 the couple would have to withdraw from savings to pay their expenses while they delayed for that one year.

Social Security is essentially an annuity with inflation protection – and the payments last as long as a retiree does. So the $12,000 cost of increasing his Social Security benefit can be compared with cost of purchasing an equivalent, inflation-indexed annuity in the private insurance market. An equivalent insurance company annuity for a 65-year-old man, which begins paying immediately and includes a survivor benefit, would cost about $13,500. …Learn More

July 30, 2019

Why are White Americans’ Deaths Rising?

Rarely does academic research make a splash with the general public like this did. A grim 2015 study, prominently displayed in The New York Times, showed death rates increasing among middle-aged white Americans and blamed so-called “deaths of despair” like opioid addiction, suicide, and liver disease.

Rising mortality, especially for white people with low levels of education, ran counter to the falling death rates the researchers found for Hispanic and black Americans. The husband and wife team who did the study proposed that “economic insecurity” might be an avenue for research into the root cause of white Americans’ deaths of despair.

A 2018 study took up where they left off and found a connection between economic conditions and some types of deaths. Researchers from the University of Michigan, Claremont Graduate University, and the Urban Institute said poor economic conditions – in the form of local employment losses – have played a role in the rising deaths since 1990 from chronic health problems like cardiovascular disease, particularly among 45 to 54 year olds with a high school education or less. However, they could not establish a connection to the rise in deaths of despair.

In a 2019 study in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, these same researchers instead focused on what is driving the growing educational disparity in life expectancy trends among whites: life expectancy is rising for those with more education but stagnating or falling for less-educated whites.

As for the health reasons behind this, they found that chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease and even cancer are critical to explaining less-educated whites’ life expectancy, and they warned against putting too much emphasis on deaths of despair. In the medical literature, they noted, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers are consistently linked to the “wear and tear” on the body’s systems due to the stress that disadvantaged Americans experience over decades, because they earn less and face adversities ranging from a lack of opportunities and inadequate medical care to substandard living environments. …Learn More

July 25, 2019

1 of 3 in Bankruptcy Have College Debt

One thing bankruptcy won’t fix is college debt, which – in contrast to credit cards – can’t usually be discharged by the courts.

One in three low-income people who have filed for bankruptcy protection from their creditors have student loans and face this predicament, according to LendEdu, a financial website.

The debt relief they can get from the courts is very limited, because the aggregate value of their non-dischargeable college loans is almost equal in value to all of their other debts combined, including credit cards, medical bills, and car loans.

Under these circumstances, a bankruptcy filing “does not sound like a financial restart,” said Mike Brown, a LendEdu blogger.

Although LendEdu analyzed data for low-income bankruptcy filers, the court’s inflexibility around student loans affects a wider swath of college-educated bankruptcy filers.

In the past, individuals were permitted to use bankruptcy to reduce their college loans. But in 1998, Congress eliminated that option unless borrowers could show they were under “undue hardship,” a legal standard that is notoriously difficult to satisfy.

While the legal requirement hasn’t changed since 1998, paying for college has become far more onerous. Americans today owe nearly $1.6 trillion in student debt, which ranks second only to outstanding mortgages. …Learn More