February 6, 2020

Can’t Afford to Retire? Not All Your Fault

Three out of four members of Generation X wish they could turn back the clock and get another shot at planning for retirement. One in three baby boomers say don’t think they’ll ever be able to retire.

“Overwhelmingly, Americans are stressed about their current – and future – financial situation,” the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors said about these new survey results.

Regrets about not planning and saving enough are enmeshed in our thinking about retirement. But it is really all your fault that you’re not getting it done?

The honest answer to that question is “no.” There are big gaps in the U.S. retirement system that make it very difficult for many to carry the responsibility it places on workers’ shoulders.

I predict some of our readers will send a comment into this blog saying, “I worked hard and planned and am comfortable about my retirement. Why can’t you?”

Granted, we should all strive to do as much as possible to prepare for old age, and many people have made enormous sacrifices in preparation for retiring. The hard truth is that some people are much better-positioned than others. Obvious examples include a public employee with a pension waiting for him at the end of his career, or a well-paid biotechnology worker with an employer that contributes 10 percent of every paycheck to her retirement savings account. These workers frequently also have employer-sponsored health insurance, which limits their out-of-pocket spending on medical care. This leaves more money for retirement saving than someone who pays their entire premium and has a $5,000 deductible.

Sure, we could all do a better job of planning out our careers when we’re first starting out. But my husband, as a Boston public school teacher, started accruing pension credits before he could’ve imagined ever getting old. He recently retired, and his pension, accumulated during 27 years of teaching, is making our life a lot easier.

Sure, we could all do a better job of planning out our careers when we’re first starting out. But my husband, as a Boston public school teacher, started accruing pension credits before he could’ve imagined ever getting old. He recently retired, and his pension, accumulated during 27 years of teaching, is making our life a lot easier.

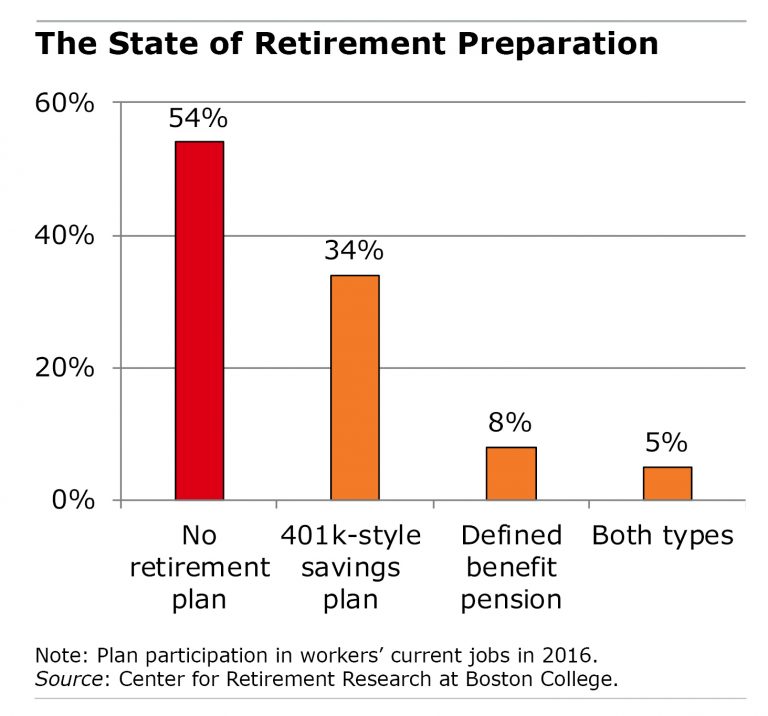

But pensions are on the wane in the private sector, and more than half of U.S. workers have neither a pension nor a 401(k) in their current job – this makes it pretty hard to save. IRAs are an option available to anyone, but human inertia makes that an imperfect solution to the problem, because people tend to procrastinate and don’t set them up. Further, working couples in which only one spouse has a 401(k) aren’t saving enough for both of them, one analysis found. …Learn More

February 4, 2020

US Life Span Lags Other Rich Countries

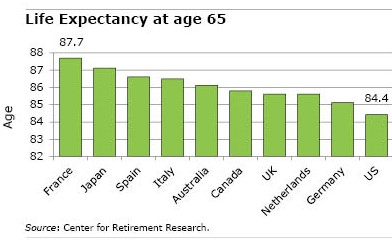

Life expectancy for 65-year-olds in the United States is less than in France, Japan, Spain, Italy, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Germany.

Life expectancy for 65-year-olds in the United States is less than in France, Japan, Spain, Italy, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Germany.

Fifty years ago, we ranked third.

First, some perspective: during that time, the average U.S. life span increased dramatically, from age 79 to 84. The problem is that we haven’t kept up with the gains made by the nine other industrialized countries, which has caused our ranking to slide.

A troubling undercurrent in this trend is that women, more than men, are creating the downdraft, according to an analysis by the Center for Retirement Research. The life expectancy of 65-year-old American women is 2½ years less than women in the other countries. The difference for men is only about a year.

The center’s researchers identified the main culprits holding us back: circulatory diseases, respiratory conditions, and diabetes. Smoking and obesity are the two major risk factors fueling these trends.

Americans used to consume more cigarettes per capita than anyone in the world. That’s no longer true. In recent years, the U.S. smoking rate has fallen sharply, resulting in fewer deaths from high blood pressure, stroke, and other circulatory diseases.

But women haven’t made as much progress as men. Men’s smoking peaked back in the mid-1960s, and by around 1990, the delayed benefits of fewer and fewer smokers started improving men’s life expectancy. Smoking didn’t peak for women until the late-1970s, and their death rate for smoking-related diseases continued to rise for many years after that, slowing the gains in U.S. life expectancy overall. More recently, this pattern has reversed so that women are now beginning to see some improvement from reduced smoking.

Obesity is a growing problem across the developed world. But in this country, the obesity rate is increasing two times faster than in the other nine countries. Nearly 40 percent of American adults today are obese, putting them at risk of type-2 diabetes and circulatory and cardiovascular diseases. …Learn More

January 30, 2020

A Cost in Retirement of No-Benefit Jobs

Only about one in four older Americans consistently work in a traditional employment arrangement throughout their 50s and early 60s. For the rest, their late careers are punctuated by jobs – freelancer, independent contractor, and even waitress – that do not have any health or retirement benefits.

Some older people are forced into these nontraditional jobs, while others choose them for the flexibility to set their own hours or telecommute. Whatever their reasons, they will eventually pay a price.

The Center for Retirement Research estimates their future retirement income will be as much as 26 percent lower, depending on how much time they have spent in a nontraditional job. During these stints, the issues are that they were not saving for retirement or accruing a pension and may have had to pay for health care out of their own pockets.

The researchers estimated the losses in retirement income to these workers by comparing them with people who have continuously been in traditional jobs with benefits. The workers in their analysis were between the ages of 50 and 62 and were grouped based on how their careers had progressed. The groups included people whose careers were primarily traditional but were interrupted by periods of nontraditional, no-benefit work, and people who spent most of their time in nontraditional jobs.

This last group lost the most: they had accrued 26 percent less retirement income by age 62 than the people who consistently held a traditional job. Who are these workers? They are a diverse mix that includes people who dropped out of high school and are marginally employed and people who are married to someone who is also employed and has benefits. …Learn More

January 28, 2020

Education Could Shield Workers from AI

Not so long ago, computers were incapable of driving a car or translating a traveler’s question from English to Hindi.

Artificial intelligence changed all that.

Computers have advanced beyond the routine work they do so efficiently on assembly lines and in financial company back offices. Today, major advances in artificial intelligence, namely machine learning, have opened up a new pathway to expanding the tasks computers can do – and, potentially, the number of workers who may lose their jobs to progress over the next 20 years.

Machine learning works this way. A computer used to identify a cat by following explicit instructions telling it a cat has pointy ears, fur, and whiskers. Now, a computer can rapidly analyze and synthesize vast amounts of data to recognize a cat, based on millions of images labeled “cat” and “not-cat.” Eventually, the machine “learns” to see a cat.

But is this technological leap fundamentally different than past advances in terms of what it will mean for workers? And what about older workers, who arguably are more vulnerable to progress, because they have less time to see the payoff from updating their outmoded skills?

The answer, according to a third and final report in a series on technology’s impact on the labor market, is that advances in machine learning are likely to affect all workers – regardless of age – in the same way that computers have over the past 40 years.

And the dividing line, according to the Center for Retirement Research, will not be age. The dividing line will continue to be education: job options are expected to narrow for workers lacking a college degree or other specialized training, while jobs requiring these credentials will expand. …Learn More

January 23, 2020

Medicaid Expansion has Saved Lives

The recent rise in Americans’ death rates is a crisis for the lowest-earning men. They are dying about 15 years younger than the highest-earners due to everything from obesity to opioids. Women with the lowest earnings are living 10 years less.

But healthcare policy is doing what it’s supposed to in the states that expanded their Medicaid coverage to more low-income people under the Affordable Care Act (ACA): helping to stem the tide by making low-income people healthier.

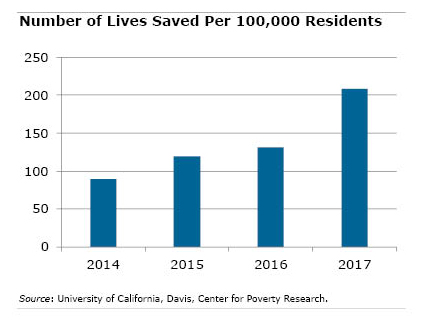

An analysis by the Center for Poverty Research at the University of California, Davis, found that death rates have declined in the states that chose to expand Medicaid coverage. The study focused on people between ages 55 and 64 – not quite old enough to enroll in Medicare.

Medicaid has “saved lives in the states where [expansion] occurred,” UC-Davis researchers found. They estimated that 15,600 more lives would have been saved nationwide if every state had covered more of their low-income residents.

Medicaid has “saved lives in the states where [expansion] occurred,” UC-Davis researchers found. They estimated that 15,600 more lives would have been saved nationwide if every state had covered more of their low-income residents.

This is one of many studies that takes advantage of the ability to compare what is happening to residents’ well-being in states that expanded their Medicaid programs with the states that did not. Progress has come on many fronts.

In expansion states, rural hospitals, which are struggling nationwide, have had more success in keeping their doors open. By covering more adults, more low-income children have been brought into the program, which one study found reduces their applications for federal disability benefits as adults. And low-income residents’ precarious finances improved in states where Medicaid expansion reduced their healthcare costs. …Learn More

January 21, 2020

Denied Disability, Yet Unemployed

Most people have already left their jobs before applying for federal disability benefits. The problem for older people is that when they are denied benefits, only a small minority of them ever return to work.

Applicants to Social Security’s disability program who quit working do so for a combination of reasons. They are already finding it difficult to do their jobs, and leaving bolsters their case. However, when older people are denied benefits after the lengthy application process, it’s very challenging to return to the labor force, where ageism and outdated skills further complicate a disabled person’s job search.

A new study looked at 805 applicants – average age 59 – who cleared step 1 of Social Security’s 5-step evaluation process: they had worked long enough to be eligible for benefits under the disability program’s rules. The researchers at Mathematica were particularly interested in the applicants rejected either in steps 4 and 5.

Of the initial 805 applicants, 125 did not make it past step 2, because they failed to meet the basic requirement of having a severe impairment. In step 3, 133 applicants were granted benefits relatively quickly because they have very severe medical conditions, such as advanced cancer or congestive heart failure.

The rest moved on to steps 4 and 5. Their applications required the examiners to make a judgment as to whether the person is still capable of working in two specific situations. In step 4, Social Security denies benefits if an examiner determines someone is able to perform the same kind of work he’s done in the past. In step 5, benefits are denied if someone can do a different job that is still appropriate to his age, education, and work experience.

In total, just under half of the 805 applicants in the study did not receive disability benefits. …Learn More

January 16, 2020

Retiring in Florida: The Villages vs Reality

May all your dreams come true.

This hope, displayed on a sign in The Villages retirement community in north central Florida, is why thousands of people flock there every year to retire.

During my annual holiday trek to visit my 84-year-old mother in Orlando, my husband and I drove her to The Villages to visit her good friend who had moved there. What struck me was the contrast between its over-the-top comforts and my mother’s modest retirement community just outside Orlando, where many of the residents, who heavily depend on their Social Security, are just barely getting by.

The differences in lifestyles reflect the retirement disparities that exist in this country and are a continuation of the disparities in our working population. But I was also struck by the similarities in what retirees – regardless of their socioeconomic status – are seeking: to live out their remaining days healthy and without worry.

The Villages is 32-square-miles of unbridled growth. The 55+ community features three Disney-like town squares – Spanish Springs, Brownwood, and Sumter Lake – with a fourth, Southern Oaks, under development. Retirees zip along in colorful golf carts through the perfectly landscaped grounds on paths that were designed for the vehicles. The residents use the golf carts to move between their tidy houses, the town squares, activity centers, and one of The Villages’ 53 golf courses and 100 pickle ball courts. There’s even a gas station for golf carts – that’s how integral they are to retirees’ lives.

It seems that the box stores and supermarkets have been placed on the edges of this sprawling development so as not to spoil the vibe – retirees drive cars to these destinations. Also on the periphery are establishments catering to the unappealing aspects of growing old: laser eye surgery centers, dialysis centers, assisted living facilities, and funeral homes. Old age is tough – even in The Villages. For example, my mother’s friend lost her husband and then – a few years later – her fiancé died.

The Villages’ creature comforts are expensive. Prices are high by the standards of Florida’s interior, ranging between $250,000 and $800,000. Residents often pay for them by selling a house up north to cash in on the appreciation. They also pay an assessment to cover the development’s infrastructure costs and a monthly fee of just over $1,000 for utilities, trash pickup and endless amenities, which, in addition to golf, include numerous activity centers, lakes for fishing, and easy access to the town centers’ restaurants, Starbucks, shopping, and movie theaters.

The Villages’ creature comforts are expensive. Prices are high by the standards of Florida’s interior, ranging between $250,000 and $800,000. Residents often pay for them by selling a house up north to cash in on the appreciation. They also pay an assessment to cover the development’s infrastructure costs and a monthly fee of just over $1,000 for utilities, trash pickup and endless amenities, which, in addition to golf, include numerous activity centers, lakes for fishing, and easy access to the town centers’ restaurants, Starbucks, shopping, and movie theaters.

But this enclave of privilege and play doesn’t reflect the reality for most retirees. My straight-talking Midwestern mom’s assessment of The Villages is, simply, “I can’t afford it.” …Learn More