December 4, 2014

How to Think About Self-Control

“Self-control” is a catch-all label for resisting all sorts of temptations, including overspending. According to a new study, controlling overspending can be broken down into three distinct behaviors:

• Setting goals such as buying a house or saving money.

• Monitoring bank statements to systematically track where your money goes.

• Committing to the goal in the face of short-term temptations to spend.

Data for the study came from a nationally representative U.S. survey of households over age 50. The survey has extensive information about the households’ finances and about each individual’s resolve to set goals, track their finances, and carry out their commitments – whether financial or non-financial.

Households lacking self-control disproportionately have lower net worth – no surprise there. The largest effect is on their liquid financial assets, such as checking and savings accounts and IRAs. Impulsive consumption “is more likely to have an immediate impact on liquid holdings than on illiquid assets,” such as property, said the researchers, who are from Goethe University in Frankfurt.

More interesting is their analysis of the role played by self-control’s three individual components. The study found that the third ingredient – the ability to stick to commitments – draws the darkest line between success and failure in accumulating net worth.

But the researchers also divided net worth into “real wealth” – homes, other property, or vehicles – and financial wealth, which is more easily liquidated than property. Commitment again proved most important in determining whether people own property. But when it comes to accumulating financial wealth, monitoring one’s finances plays the largest role.

Everyone talks about self-control. This study clarifies what it is.

Learn More

December 2, 2014

Curbing Debt: It’s Not What You Know

The biggest financial hurdle facing workers with low incomes is just that: inadequate income to meet their daily needs.

Low-income households are further tripped up by their greater tendency to borrow at high interest rates – rates they are the least able to afford in the first place.

Some academic research blames this on poor financial literacy. But a new study out of Northern Ireland examines two separate aspects of financial literacy and finds the problem is not a lack of knowledge but rather an absence of money management skills.

Among “financially vulnerable” people, the study concluded, “money management skills are important determinants of consumer debt behavior” and “numeracy has almost no role to play.”

The study involved researchers conducting one-hour, face-to-face interviews in low-income neighborhoods in Belfast. They interviewed 499 people whose average gross earnings were the equivalent of $567 per week or less. …Learn More

November 27, 2014

A Time for Family and Friends

The staff at Squared Away wish our readers a Happy Thanksgiving with your family and friends.

Our twice-weekly articles will resume next Tuesday.Learn More

November 25, 2014

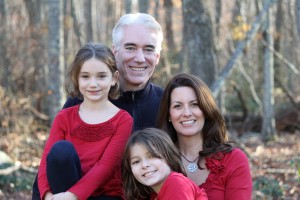

Alzheimer’s: a Financial Plan Revamped

Ken Sullivan’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease at age 47 unleashed a torrent of feelings: shock, isolation, fear. It’s probably why he lost his demanding job at a large financial company.

The diagnosis was also emotionally devastating for his wife, Michelle Palomera.

But for both of them, it was a rude awakening to the myriad financial preparations required for Alzheimer’s. Even though both are financial professionals, they had no idea how complex it would be to revise their existing financial plan, how hard it would be to find professionals with the specific legal and financial expertise to help them, or how long this project would take – 17 months and counting.

“This disease has so many layers and aspects to it,” Palomera said.

The risk to an older individual of getting Alzheimer’s is only 10 percent – and early-onset like Sullivan’s is even rarer. But when there is a diagnosis, one issue is the lack of a centralized system for managing care and coordinating the myriad professionals and organizations involved. These range from the medical people who diagnose and treat an Alzheimer’s victim to health insurers, attorneys, social workers, disability and long-term care providers, and the real estate agent who may be needed if a victim or the family decides they can’t remain in their home.

Sullivan and Palomera had always shared their family’s financial duties. But Sullivan’s new struggles with details and spreadsheets left these tasks entirely on Palomera’s shoulders – all while juggling her job as a managing director for a financial company. “If something were to happen to me, I have to be really air tight on having everything squared away so the trustee – someone – can manage the situation for our daughters and Ken,” she said.

After Sullivan’s June 8, 2013 diagnosis, the couple called family to gently break the news. Their next calls were to a disability attorney and a financial planner. They’ve since gone through four estate attorneys to find one who could answer their questions and suggest the best options for themselves and daughters Leah, 9, and Abby, 11.Learn More

November 20, 2014

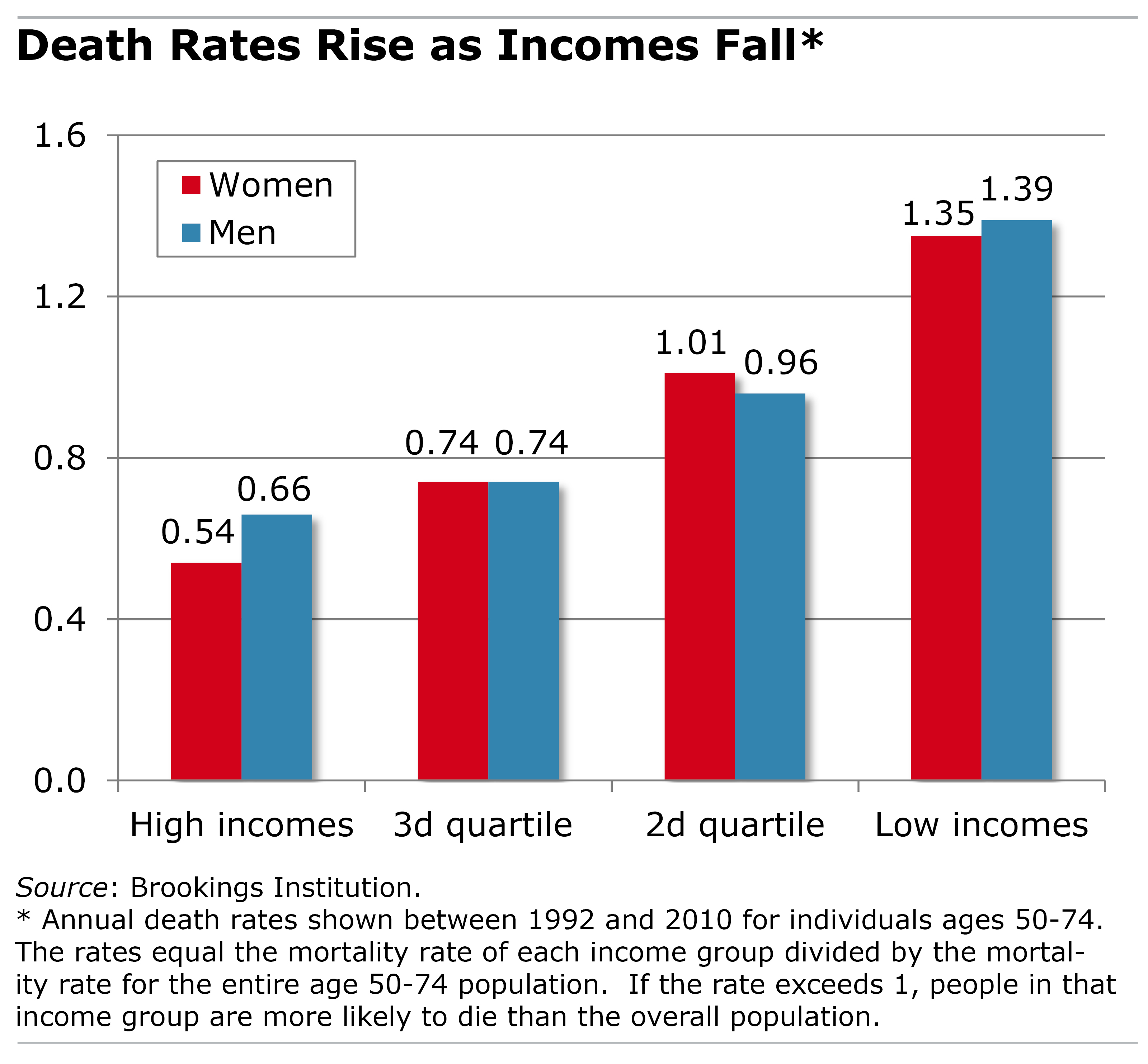

Income and Disparate Death Rates

The differences in Americans’ longevity, depending on one’s income level, are striking.

The annual death rates for 50- to 74-year-old men and women with the lowest earnings are more than double what they are for high earners.

This gap in life spans, which is well-documented in the research literature, has been growing with each new generation. A recent study digs deeper to uncover specific ailments, such as heart disease, that may be driving the growing disparity.

Brookings Institution researchers Barry Bosworth, Gary Burtless, and Kan Zhang used data from a nationally representative sample of almost 32,000 older Americans that included the causes of individual deaths occurring between 1992 and 2010. The survey contains detailed information about the cause and timing of the deaths, as well as interviews with family of the survey participants after they die.

Brookings Institution researchers Barry Bosworth, Gary Burtless, and Kan Zhang used data from a nationally representative sample of almost 32,000 older Americans that included the causes of individual deaths occurring between 1992 and 2010. The survey contains detailed information about the cause and timing of the deaths, as well as interviews with family of the survey participants after they die.

The researchers compared the mortality rates linked to specific diseases for high- and low income people, defined as those whose earnings in their prime working years fell either above or below the median, or middle, income. They found that the risk of dying from the nation’s leading causes of death – cancer and heart conditions – has declined significantly for high-income Americans, both men and women. No such improvements were evident, however, for low-income men and women. …Learn More

November 18, 2014

Pension Cuts Could Hurt Worker Quality

Cuts in public pensions taking place around the country could reduce the ability of state and local governments to recruit and retain top-quality workers, according to new findings by the Center for Retirement Research, which sponsors this blog.

Economists have long argued that pensions and worker quality are related. Pensions, like paychecks, are a form of compensation, one that particularly appeals to workers with the foresight to value financial security in a retirement still decades away. And these are often better, more productive workers.

To examine the effect of pension generosity on worker quality, the Center’s researchers first had to find good measures of each. For worker quality, they used U.S. Census Bureau survey data on workers who have moved between the public and private sectors. The data show that private-sector wages paid to those leaving government were consistently higher than the private-sector wages of people leaving the private sector to work in government – about 7 percent higher, on average, between 1980 and 2012. This wage difference represents the “quality gap” among workers. …Learn More

November 13, 2014

Trusting Souls Want Financial Advice

Here’s a conundrum: Americans struggle to save for retirement or reduce their credit card spending. But only about one out of three seeks help with financial issues.

So what lies at the heart of our decisions about whether and when to seek help? Trust.

In the video below, Angela Hung, director of the RAND Center for Financial and Economic Decision Making, describes research showing that people who trust financial institutions – the markets, financial services companies, brokers – are also more likely to ask for advice from a financial adviser or similar professional.

Further, Hung’s research found that people who trust the industry are also “more likely to be satisfied with their financial service provider.” Watch the video for Hung’s explanation of an interesting experiment that explores the circumstances under which people follow the advice once it’s given to them.