Posts Tagged "retirement"

June 4, 2015

Workers See Regular, Roth 401ks as Same

Due to differing tax treatments, each $1,000 placed into a traditional, tax-deductible 401(k) costs less today than $1,000 placed into a Roth 401(k), but that Roth will provide more money in retirement.

New research indicates that workers don’t recognize this difference between the two types of employer-sponsored retirement accounts when deciding how much to save.

A $1,000 contribution to a traditional 401(k) costs the worker less than $1,000 in take-home pay, because the income tax hit on the $1,000 will be delayed until the money is withdrawn from the account. But a $1,000 contribution to a Roth 401(k) costs exactly $1,000 in take-home pay, because the worker has to pay income taxes on it up front. The Roth funds, including the investment returns, will not be taxed when they’re withdrawn.

A Roth 401(k) might be thought of as shifting additional money into the future, allowing people to spend and consume more in retirement. (This assumes the same tax rate over a worker’s lifetime.)

The upshot: to get a set amount of after-tax money for retirement, workers could contribute less to a Roth than to a traditional 401(k). But that’s not what they do. …Learn More

May 28, 2015

Annuities: Useful but Little Understood

The general public is very cool on annuities. But many economists like the idea of retirees using some portion of their savings to buy them.

Annuities, with their fixed monthly payments, may be the best way to ensure retirees’ savings last just as long as they do. Otherwise, they may either spend it too fast and deplete their savings prematurely or spend too conservatively, depriving themselves of necessities in their old age.

New research suggests that one reason retirees don’t buy annuities is because they have great difficulty figuring out what they’re worth. When they try to figure this out, they bump up against their own cognitive limitations – limitations that only worsen with age.

In the study, 2,210 adults over age 18 were asked to estimate the value of a monthly annuity familiar to most workers: Social Security benefits. First, the research subjects were asked if they would pay $20,000 to “buy” a $100 increase in their monthly Social Security benefits. If the person said no, the survey repeated the question with a lower amount, eventually zeroing in on what this additional $100 benefit was worth to them. Next, the research subjects were asked to reduce – or “sell” – their monthly benefits by $100 in return for a specific dollar amount paid to them upfront.

In theory, the buy and sell prices they finally arrived at should be equal. But there was an enormous gap between the two. The median price research subjects were willing to pay was $3,000, and the median price at which they would sell was $13,750. There was also a wide range of sales prices among the individual participants: some would accept $1,500 or less, while others wanted $200,000 or more. …Learn More

April 16, 2015

Will Boomers Delay Social Security?

A 1983 reform to Social Security is now in full swing for baby boomers: they must wait at least until their 66th birthday to claim their full pension benefits.

But is the gradual increase in the program’s so-called full retirement age – it was 65 for prior generations – having any effect on when boomers retire?

Why people decide to retire when they do is complicated, and economists have tried for years to understand this. Americans are working slightly longer than they did in the mid-1990s, with the average retirement age rising from 62 to 64 for men and from 60 to 62 for women (though this trend may be stalling). Myriad possible explanations for retiring later include the decline of traditional pensions, greater longevity, healthier older workers, and a more educated labor force.

Another reason could be the 1983 reform delaying the age at which baby boomers in this country are allowed to claim their full Social Security pensions, a reason supported by a new study of similar reforms to Switzerland’s government pensions.

The researchers found that a one-year increase in Switzerland’s full retirement age, or FRA, for women is associated with a half-year delay in when women retire and when they claim their full government pensions. …Learn More

April 14, 2015

Even in Nursing, Men Earn More

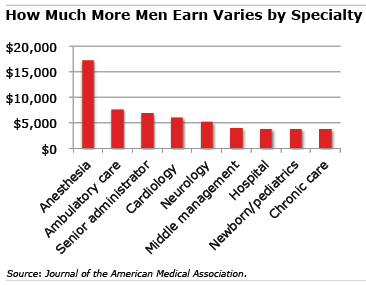

The nursing profession is predominantly women, but it’s the male nurses who earn more – $5,148 more per year on average.

“Male RNs out-earned female RNs across settings, specialties, and positions with no narrowing of the pay gap over time,” according to a salary comparison from 1998 through 2013 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Other research has revealed pay gaps in teaching, another women-dominated profession.

Today is Equal Pay Day, and the media is replete with reminders that American women earn 77 cents for every dollar that men earn. Nursing is the single largest profession in the growing health care sector, and the pay gap affects some 2.5 million women employed in a profession established in 19th century London by Florence Nightingale, who wrote “Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not.”

The importance of a woman’s earnings level goes beyond the obvious implications for her current standard of living. Earnings are also key to how much she can accumulate over a lifetime.

The largest pay disparity is for nurse anesthetists: men earn $17,290 more than their female counterparts. The only category in which women out-earn – by $1,732 – is university professors in the nursing field. The researchers isolate the role a nurse’s sex plays by controlling for demographic characteristics such as education level, work experience and other factors that also influence how much someone earns. Only about half of the gap between men and women was explained by these identifiable factors, leaving half unexplained.

The chart below shows pay gaps, by type of nurse specialty.

April 9, 2015

Retirement Coverage Expanded: UK vs US

President Obama signed a January memo officially launching his MyRA program to encourage saving by low-income and other Americans who lack a retirement plan through their employers.

The United Kingdom is also addressing pension shortfalls for uncovered workers in a much more ambitious way. The U.K. program, put in place in 2012, has two key provisions that MyRA lacks: it automatically enrolls workers so more will save in the first place, and it provides them with matching contributions.

The U.K. program has enrolled 1.8 million of the 4 million workers targeted, primarily at small employers. A 2014 study by the Center for Retirement Research, which supports this blog, described the program and compared it with MyRA.

The United Kingdom’s retirement income problems largely stem from the contraction of the government’s retirement system. A first stab at improving retirement income security came in 2001, when the government mandated that employers with five or more workers offer a low-cost retirement savings plan that workers could volunteer to join. That program gained little traction among workers or financial firms.

The 2012 reform was much bolder. In addition to mandating a 3 percent employer match (starting in 2017), the government matches 1 percent, with both matches contingent on the employee saving 4 percent of his earnings. To manage the program and offer a low-cost savings plan to employers, the National Employment Savings Trust, or NEST, was established. …Learn More

March 12, 2015

Navigating Taxes in Retirement

The tax landscape shifts suddenly when most Americans leave the labor force to retire. The single most important thing to remember is that income taxes can fall dramatically, because retirement incomes are typically lower and because all or a portion of your Social Security benefits will be tax-exempt.

This was among the tax insights supplied by Vorris J. Blankenship, a retirement tax planner near Sacramento, California, who has just finished the 2015 edition of his 5-inch thick “Tax Planning for Retirees.” The following is an edited version of tax information he supplied to Squared Away:

Lower taxes in retirement. Brian and Janet are a hypothetical couple renting an apartment in Nevada, a state with no income tax. In 2013, Brian earned $40,000 at his job, and Janet’s wages were $20,000, for a total income of $60,000. They took the standard deduction on their federal tax return and paid income tax of $5,111.

Brian retired on December 31, 2013. In 2014, he received Social Security payments of $15,000 – $2,750 of which was taxable – and a fully taxable pension from his former employer of $10,000. About one-third of retirees pay some income taxes on their Social Security benefits, because their retirement income exceeds certain thresholds in the tax code.

In 2014, Janet again earned $20,000, but the couple’s total household income declined to $45,000 from $60,000. They took the standard deduction on their federal tax return and paid income tax of only $1,248.

The 75 percent reduction in their taxes is much larger than the 25 percent decline in their income after Brian retired. …Learn More

March 10, 2015

9 Measures of U.S. Economic Inequality

The interactive chart above illustrates the increasing U.S. disparity over the past 50 years between how much wealth the rich own – shown on the right side of the chart – and everyone else on the left.

The vast majority of Americans build wealth week by week, saving a little bit of their paychecks. Workers set aside wealth in less obvious ways too, by contributing some of that paycheck to Social Security and possibly paying down a mortgage.

Differences in earnings add up over a lifetime and contribute to how much wealth people are able to accumulate. This is explored in the Urban Institute’s series of nine charts, including the one above. Take the earnings trend over a half century shown in Chart No. 2 on the Urban Institute’s website: the nation’s top-paid workers have enjoyed increasing incomes, while wages have essentially been flat for those at the bottom. [All income and wealth data are in constant 2013 dollars and are comparable.]

The charts, when taken together, also illustrate how much larger is the wealth disparity between the top and bottom than is the earnings disparity. This is especially true of racial inequalities, even when the researchers control for income and age.

In Chart No. 5 on the Urban Institute’s website, the total value of the lifetime earnings of the typical white baby boomer born between 1943 and 1951 is $2 million – 30 percent more than African-Americans’ lifetime earnings of $1.5 million.

The typical white American families’ retirement savings (Chart No. 7) is $130,472 – seven times more than African-American families at $19,049. [Wealth data were provided only for families, not for individuals.] A report by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reached similar conclusions about the income and wealth gaps for black families.

To see all nine of the Urban Institute’s charts and its report, click here.Learn More