Posts Tagged "saving"

January 17, 2013

401(k)s Bleeding Cash

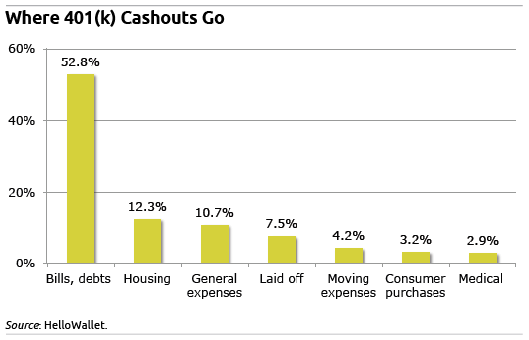

HelloWallet’s survey landed with a thud in the media this week: one in four U.S. households with a 401k or IRA raided it to cover necessities.

The vast majority of raids are cash withdrawals, not loans – $60 billion in cash in 2010. These grim statistics throw weight behind those who argue we are watching a retirement crisis unfold in slow motion. The pressures on saving are aggravated by stubbornly high long-term unemployment: layoffs explain why 8 percent pulled out cash. But the Great Recession isn’t the only culprit.

Wages, adjusted for inflation, have declined over the past decade, health costs have soared, and consumers remain heavily dependent on their credit cards. In this environment, no wonder saving is often viewed as a luxury.

The 2010 data reveal behavior at a time individuals were still smarting from Wall Street’s financial crisis. But back in 2004, the average 401k balance for all boomers age 55 to 64 was only $45,000 – it was only slightly lower by 2010.

To put that $60 billion in perspective, it is about half the amount U.S. employers put into 401(k) plans on their employees’ behalf that year.

Click “Learn More” to see more data on the cash withdrawals. Readers, what do you think is driving them higher?Learn More

November 8, 2012

Women’s Pay Gap Explained

Lower pay for women came up – where else! – in the foreign policy debate between President Obama and Governor Romney. It affects women’s living standards, single mothers’ ability to care for their children, and everyone’s retirement – husbands and wives.

To understand why women earn 77 cents for every dollar earned by men, Squared Away interviewed Francine Blau of Cornell University, one of the nation’s top authorities on the matter. A new collection of her academic work, “Gender, Inequality, and Wages,” was published in September.

Q: How has the pay gap changed over the years?

Blau: For a very long time, the gender-pay ratio, which is women’s pay divided by men’s pay, was around 60 percent – in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Around the 1980s, female wages started to rise relative to male wages. In 1990, the ratio was 72 percent – that was quite a change, from 60 to 72 in 10 years. We continued to progress but it is less dramatic. In 2000, it was 73 percent. Now it’s 77 percent – that’s the figure that came up in the debate.

Q: Why do women earn less?

Blau: There are two broad sets of factors: the first is human capital and the factors that contribute to productivity and the second is discrimination in the labor market. Women have traditionally been less well qualified than men. The biggest reason here is the experience gap between men and women. Traditionally, women moved in and out of the labor force, and that lowered their wages relative to men.

But when we do elaborate studies – my recent study with Lawrence Kahn in 2006, for example – we find that when we take all those productivity factors into account we can’t fully explain the pay gap. The unexplained portion is fairly substantial and is possibly due to discrimination, though it could be various types of unmeasured factors. So in the 1998 data used in our 2006 article, women were making 20 percent less than men per hour. When we take human capital into account, that figure falls to 19 percent. When we add controls for occupation and industry – men and women tend to be in different occupations and industries – we can get a pay gap of 9 percent. This unexplained gap of 9 percent is potentially due to discrimination in the workplace. …Learn More

October 23, 2012

401(k)s “Top” Financial Priority. Really.

A large majority of people in a survey released last week identified saving for retirement as their top financial priority. If that’s the case, then why aren’t Americans saving enough?

Stuart Ritter, senior financial planner for T. Rowe Price, the mutual fund company that conducted the survey, has some theories about that. Squared Away is also interested in what readers have to say and encourages comments in the space provided at the end of this article.

But first the survey: about 72 percent of Americans identified saving for retirement as “their top financial goal,” with 42 percent saying that a contribution of at least 15 percent of their pay is “ideal.”

Yet 68 percent said they are saving 10 percent or less, which Ritter called “not very much.” The average contribution is about 8 percent of pay, according to Fidelity Investments, which tracks client contributions to the 401(k)s it manages.

The Internal Revenue Service last week increased the limit on contributions to 401(k) and 403(b) retirement plans from $16,500, to $17,000. The so-called “catch-up” contribution available to people who are age 50 or over remains unchanged at $5,500.

The question is: why do Americans give short shrift to their 401(k)s, even as people become increasingly aware that their dependence on them for retirement income grows? Ritter offered a few theories in a telephone interview last week:

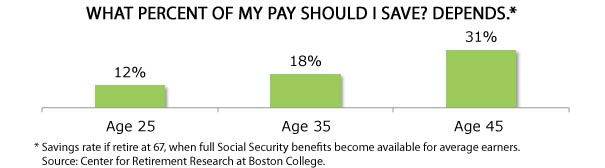

- The financial industry is partially to blame. “We have done a really good job of conveying to people how important saving for retirement is,” he said, “but what we haven’t done as good a job of is telling them how much to save.”

Employers may also share blame. Further confusing the issue, the savings rate depends on when the employee starts saving – the percent of pay is lower for those who start in their 20s than for someone who waits until they’re 45. …

September 27, 2012

Paying Mortgage Faster Not Best Option

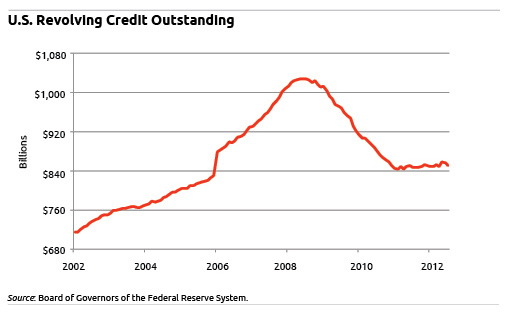

Americans have been paying down their high-interest credit cards like crazy. Once you do, financial advisers say, think hard about the best use of that spare cash.

With mortgage interest rates at historic lows – they’re scraping 3.5 percent on 30-year fixed loans and 2.8 percent for 15 years – paying extra on the mortgage should no longer be a priority. This simplifies what is a difficult decision for many of us: what’s next?

Saving for retirement and paying off student loans are now the top priorities, in that order, according to two financial advisers interviewed by Squared Away. But paying off the mortgage is a mistake that many people continue to make: mortgage debt outstanding has also declined in recent years, from $11.1 trillion in 2008 to $10 trillion currently, according to the Federal Reserve.

“Paying off a mortgage – I’m not a big fan of that,” said John Scherer of Trinity Financial planning near Madison, Wisconsin. He proposes that his clients funnel the extra money that had been used to pay credit cards into other personal finance “buckets.” …

September 11, 2012

Motivation to Save: A Simple Solution?

Quiz: by socking away $400 per month, earning 10 percent on your money, you can save $302,412 in 20 years. So, how much would you have in that same account in 40 years?

Yes, it’s more than double. But how much more?

Most Americans can’t do the math, explains Craig McKenzie of the University of California, San Diego’s Rady School of Management, in this video. And if they can’t do the math, then they are unable to comprehend how much easier their lives would be if they took advantage of the enormous benefits of starting to save early for their retirement.

That’s hardly surprising. What is surprising, however, is that McKenzie, a cognitive psychologist by training, experimented with a “simple, straightforward intervention” to get the point across to research subjects of the large boost to saving of earning compound interest over many years. Even better, it succeeded in motivating them to save, he said.

The solution is, as promised, simple – so easy that employers who offer 401ks, as well as mutual fund companies, banks and credit unions, could easily implement it…

Learn More

September 4, 2012

Flatline: U.S. Retirement Savings

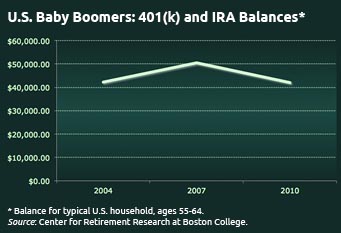

Baby boomers’ balances in 401k and IRA accounts have barely budged for most of the past decade.

In 2004, the typical U.S. household between ages 55 and 64 held just over $45,000 in their tax-exempt retirement plans. Plan balances for people who fell in that age group in 2007 rose but settled back down after the biggest financial crisis in U.S. history. In 2010, they were $42,000, a few bucks lower than 2004 balances.

These are among the reams of sobering data contained in the Federal Reserve’s 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances released in June. The $42,000 average balance is for all Americans – it includes the more than half of U.S. workers who do not participate in an employer-sponsored savings program.

There’s more bad news buried in the SCF: the value of other financial assets such as bank savings accounts dropped in half, to $18,000. And hardship withdrawals from 401(k)s have increased, to more than 2 percent of plan participants, from 1.5 percent in 2004.

There’s more bad news buried in the SCF: the value of other financial assets such as bank savings accounts dropped in half, to $18,000. And hardship withdrawals from 401(k)s have increased, to more than 2 percent of plan participants, from 1.5 percent in 2004.

So, where did all that wealth created by the longest economic boom in U.S. history go? The 2008 financial collapse didn’t help. But we can also blame the baby boom culture. Click here to read a year-ago article that examines the cultural reasons for the troubling condition of our retirement system.

To receive a weekly email alerts about new blog posts, click here.

There’s also Twitter @SquaredAwayBC, or “Like” us on Facebook!Learn More

August 23, 2012

401(k) Tax Break May Be Weak Incentive

The typical American household approaching retirement age had just $42,000 saved in its 401(k) in 2010. This raises the question: Does the federal tax incentive designed to spur savings even work?

In what one retirement expert called “landmark” research, a new study has found that employers’ automatic enrollment and other employee mandates are far more effective ways to increase retirement savings than the federal tax exemption granted for retirement-fund contributions.

Harvard University Professors Raj Chetty and John Friedman, together with Soren Leth-Petersen and Torben Nielsen at the University of Copenhagen, tested the impact of both types of incentives on an enormous sample of 4.3 million people in Denmark. Chetty said the findings also hold implications for the United States.

They found that every $1 increase mandated for retirement savings – in this case, by a temporary Danish policy that required workers to contribute 1 percent of their earnings to government pension savings accounts – spurred 86 cents in additional savings by individuals. In contrast, the Danish government’s tax subsidy, which is very much like our own 401(k) tax break, spurred only 20 cents more in savings.

“This is a landmark study,” Dartmouth College professor Jonathan Skinner said about the paper, presented during the Retirement Research Consortium’s conference in Washington in early August. “I can’t emphasize enough how important this study is in terms of how retirement policies work.” …Learn More