Posts Tagged "work"

September 3, 2019

Second Careers Late in Life Extend Work

Moving into a new job late in life involves some big tradeoffs.

What do older people look for when considering a change? Work that they enjoy, fewer hours, more flexibility, and less stress. What could they be giving up? Pensions, employer health insurance, some pay, and even prestige.

Faced with such consequential tradeoffs, many older people who move into second careers are making “strategic decisions to trade earnings for flexibility,” concluded a review of past studies examining the prevalence and nature of late-life career changes.

The authors, who conducted the study for the University of Michigan’s Retirement and Disability Research Center, define a second career as a substantial change in an older worker’s full-time occupation or industry. They also stress that second careers involve retraining and a substantial time commitment – a minimum of five years.

The advantage of second careers is that they provide a way for people in their late 40s, 50s, or early 60s who might be facing burnout or who have physically taxing jobs to extend their careers by finding more satisfying or enjoyable work.

Here’s what the authors learned from the patchwork of research examining late-life job changes:

People who are highly motivated are more likely to voluntarily leave one job to pursue more education or a position in a completely different field, one study found. But older workers who are under pressure to leave an employer tend to make less dramatic changes.

One seminal study, by the Urban Institute, that followed people over time estimated that 27 percent of full-time workers in their early 50s at some point moved into a new occupation – say from a lawyer to a university lecturer. However, the research review concluded that second careers are more common than that, because the Urban Institute did not consider another way people transition to a new career: making a big change within an occupation – say from a critical care to neonatal nurse. “Unretiring” is also an avenue for moving into a second career.

What is clear from the existing studies is that older workers’ job changes may involve financial sacrifices, mainly in the form of lower pay or a significant loss of employer health insurance. But they generally get something in return: more flexibility. …Learn More

August 6, 2019

People in their Prime are Working Less

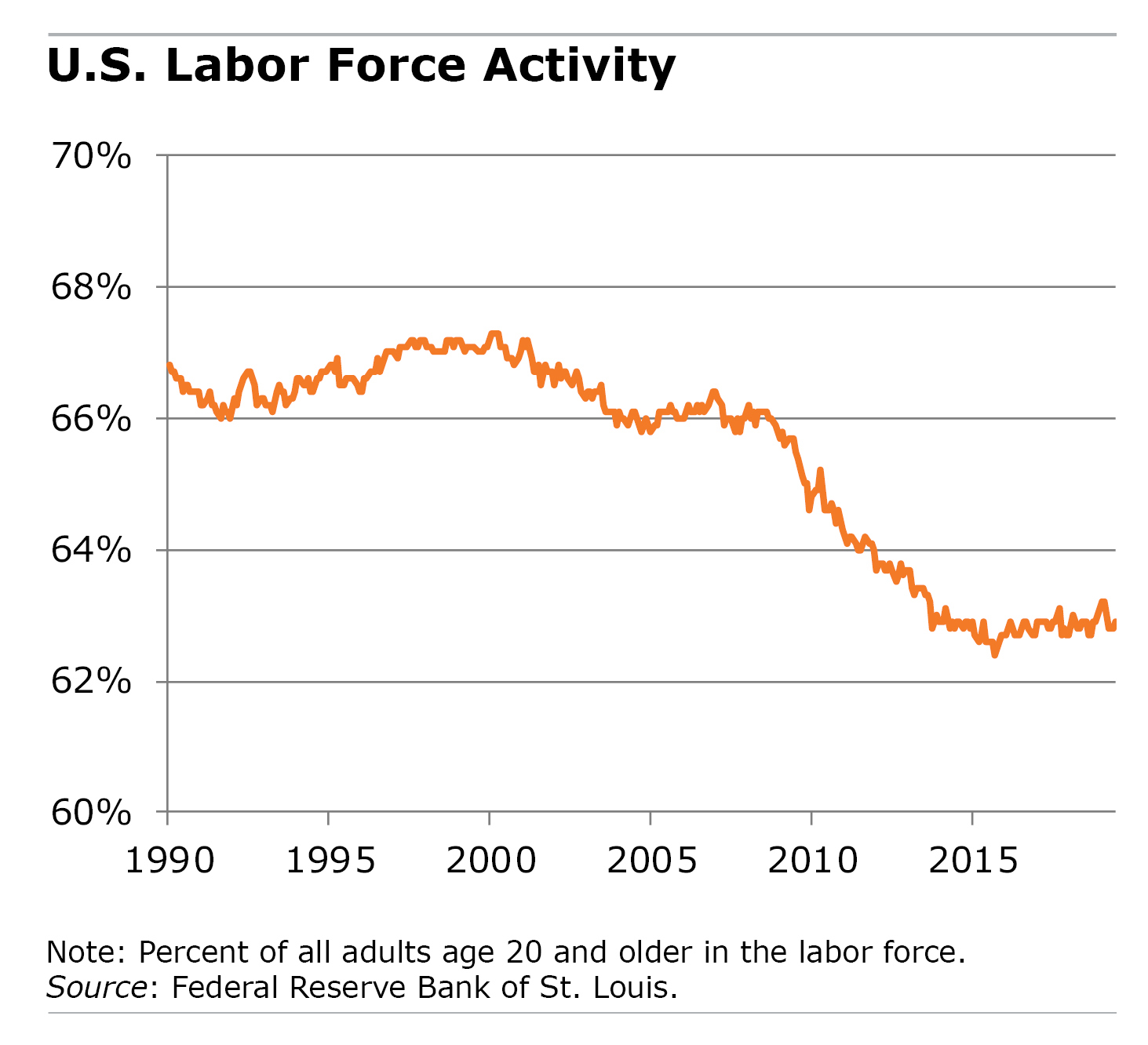

The decline in Americans’ labor force activity started around the year 2000 and accelerated after the 2008-2009 recession. Labor force participation is now at its lowest level since the 1970s.

The decline in Americans’ labor force activity started around the year 2000 and accelerated after the 2008-2009 recession. Labor force participation is now at its lowest level since the 1970s.

The main reason for the drop is our aging population. But the news in a systematic review of current research in this area is a more troubling trend that’s also driving it: people in their prime working years – ages 25 through 54 – are falling out of the labor force.

Prime-age men are the most active members of the labor force. Yet in 2017, only 89.1 percent of them were either working or seeking a job, down from 91.5 percent in 2000, according to the review by University of Southern California economists.

Prime-age women’s labor force activity also fell, to 75.2 percent in 2017 from about 77 percent in 2000. This decline ends decades in which women were streaming into the nation’s workplaces at an increasing rate. One possible reason for the leveling off is the scarcity of family-friendly policies, including more generous childcare assistance.

The forces pushing and pulling various groups in and out of the labor force make it difficult to pin down the primary reasons for the overall drop in participation. The decline among prime-age men and women may be tied to opioid addiction, alcoholism, and suicide. Other studies point to the surge in incarcerations of black men.

And while technological advances like robots and growing trade with China have increased the need for many highly skilled workers, they have reduced the demand for less-educated, lower-paid people, including U.S. factory workers, in their peak working years. The resulting fall in their wages has also made work less attractive to them. …Learn More

July 16, 2019

Spotlight on Our Research, Aug. 1-2

Topics for this year’s Retirement and Disability Research Consortium meeting include the opioid crisis, retirement wealth inequality over several decades, trends in Social Security’s disability program, and the impacts of payday loans, college debt, and mortgages on household finances.

Researchers from around the country will present their findings at the annual meeting in Washington, D.C. Anyone with an interest in retirement and disability policy is welcome. Registration will be open through Monday, July 29. For those unable to attend, the event will be live-streamed. The agenda lists all of the studies.

Here are a few:

- Why are 401(k)/IRA Balances Substantially Below Potential?

- The Impacts of Payday Loan Use on the Financial Well-being of OASDI and SSI Beneficiaries

- The Causes and Consequences of State Variation in Healthcare Spending for Individuals with Disabilities

- Forecasting Survival by Socioeconomic Status and Implications for Social Security Benefits

- What is the Extent of Opioid Use among Disability Applicants? …

April 23, 2019

Boomers with Disabilities Often Retire

One in four workers in their mid-50s will eventually encounter difficulties on the job, because their bodies start breaking down or they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

When a new, disabling condition is long-lasting, 63-year-olds – still a young age to be retiring – are two times more likely to stop working than other people their age, according to a new study by Mathematica, a Princeton, N.J., research firm.

The researchers started out with a fairly healthy group of 55-year-olds and followed their career paths through age 67. Strikingly, even people as young as 59 who have experienced a new work-limiting health condition leave the labor force at a much higher rate than those who did not. It’s inevitable that many, though not all, of the oldest workers in this group decide to retire, rather than find a new job.

Of course, the nature of the work factors into whether someone decides they have to retire. When older workers have physically demanding jobs, they are more likely to report a new disabling condition, the study found. It can be extremely difficult to soldier on in occupations such as construction or heavy industry.

With less physical jobs, however, it is more feasible to work longer even with a disability. For example, a lawyer or administrative assistant could conceivably keep working, even if it became difficult to walk.

In addition to the physical challenges, disability couldn’t come at a worse time financially for baby boomers, a significant minority of whom are not well-prepared for retirement.

They would benefit from staying in the labor force as long as possible to save more and hold out for a larger Social Security check every month. …Learn More

February 26, 2019

Baby Boomer Labor Force Rebounds

One way baby boomers adjust to longer lifespans and inadequate retirement savings is to continue working. There’s just one problem: it can be more difficult for some people in their 50s and 60s to get or hold on to a job.

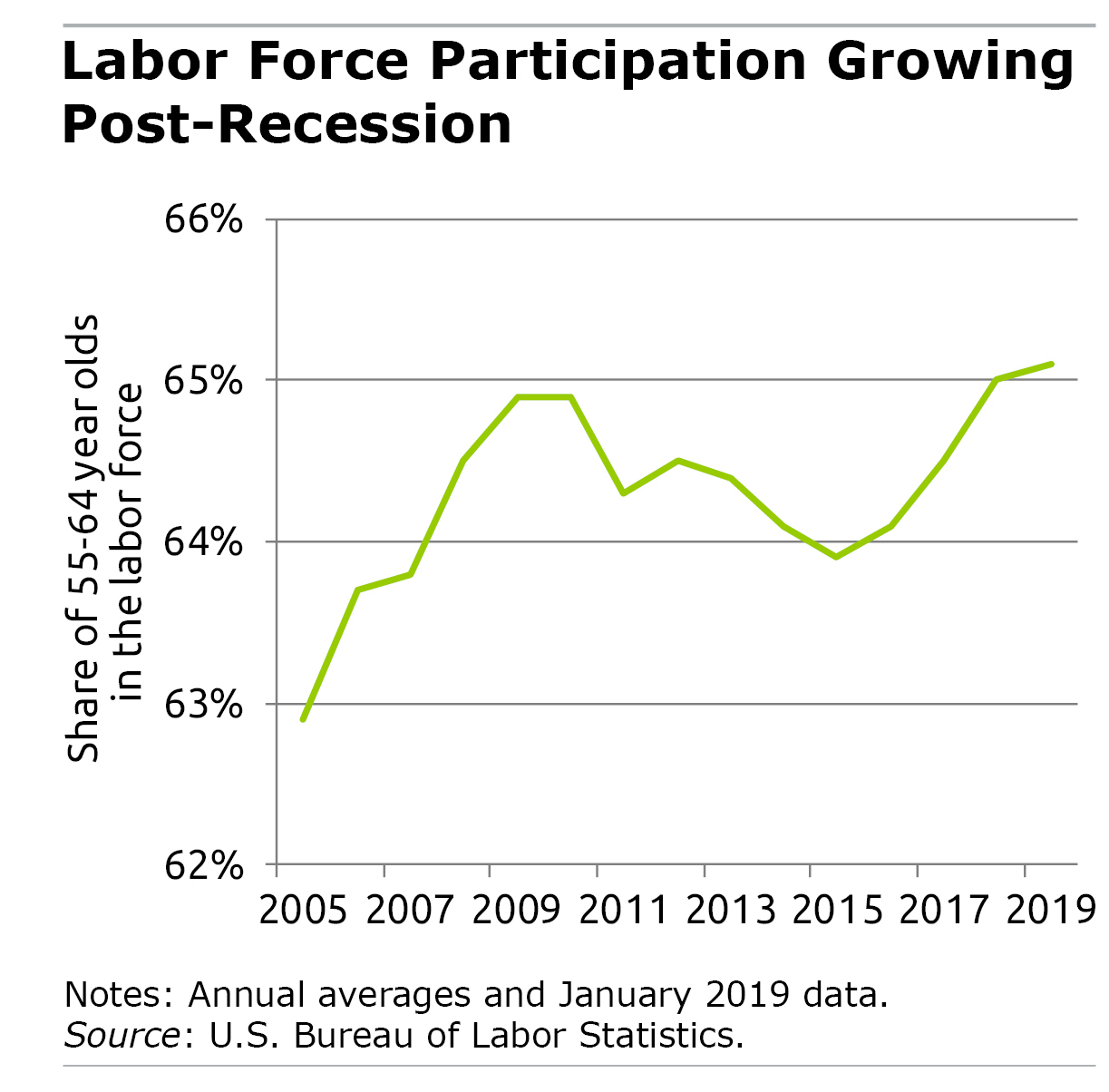

But things are improving. The job market is on a tear – 300,000 people were hired in January alone – and baby boomers are jumping back in. A single statistic illustrates this: a bump up in their labor force participation that resumes a long-term trend of rising participation since the 1980s.

But things are improving. The job market is on a tear – 300,000 people were hired in January alone – and baby boomers are jumping back in. A single statistic illustrates this: a bump up in their labor force participation that resumes a long-term trend of rising participation since the 1980s.

In January, 65.1 percent of Americans between ages 55 and 64 were in the labor force, up smartly from 63.9 percent in 2015. This has put a halt to a downturn that began after the 2008-2009 recession, which pushed many boomers out of the labor force. The labor force is made up of people who are employed or looking for work.

The recent gains don’t seem transitory either. According to a 2024 projection by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the older labor force will continue to grow. The biggest change will be among the oldest populations: a 4.5 percent increase in the number of 65- to 74-year olds in the labor force, and a 6.4 percent increase over age 75. …Learn More

August 30, 2018

Why US Workers Have Lost Leverage

A 1970 contract negotiation between GE and its unionized workforce is unimaginable today.

A strike then slowed production for months at 135 factories around the country. With inflation running at 6 percent annually, the company offered pay raises of 3 percent to 5 percent a year for three years. The union rejected the offer, and a federal mediator was brought in. GE eventually agreed to a minimum 25 percent pay raise over 40 months.

“They said we couldn’t, but we damn sure did it,” one staffer said about his union’s victory.

Former Wall Street Journal editor Rick Wartzman tells this story in his book about the rise and fall of American workers through the labor relations that have played out at corporate stalwarts like GE, General Motors, and Walmart.

Critics use examples like GE to argue that unions had it too good – and they have a point. But that’s old news. What’s relevant today is that the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, and blue-collar and middle-class Americans seem barely able to keep their heads above water even in a long-running economic boom.

Critics use examples like GE to argue that unions had it too good – and they have a point. But that’s old news. What’s relevant today is that the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, and blue-collar and middle-class Americans seem barely able to keep their heads above water even in a long-running economic boom.

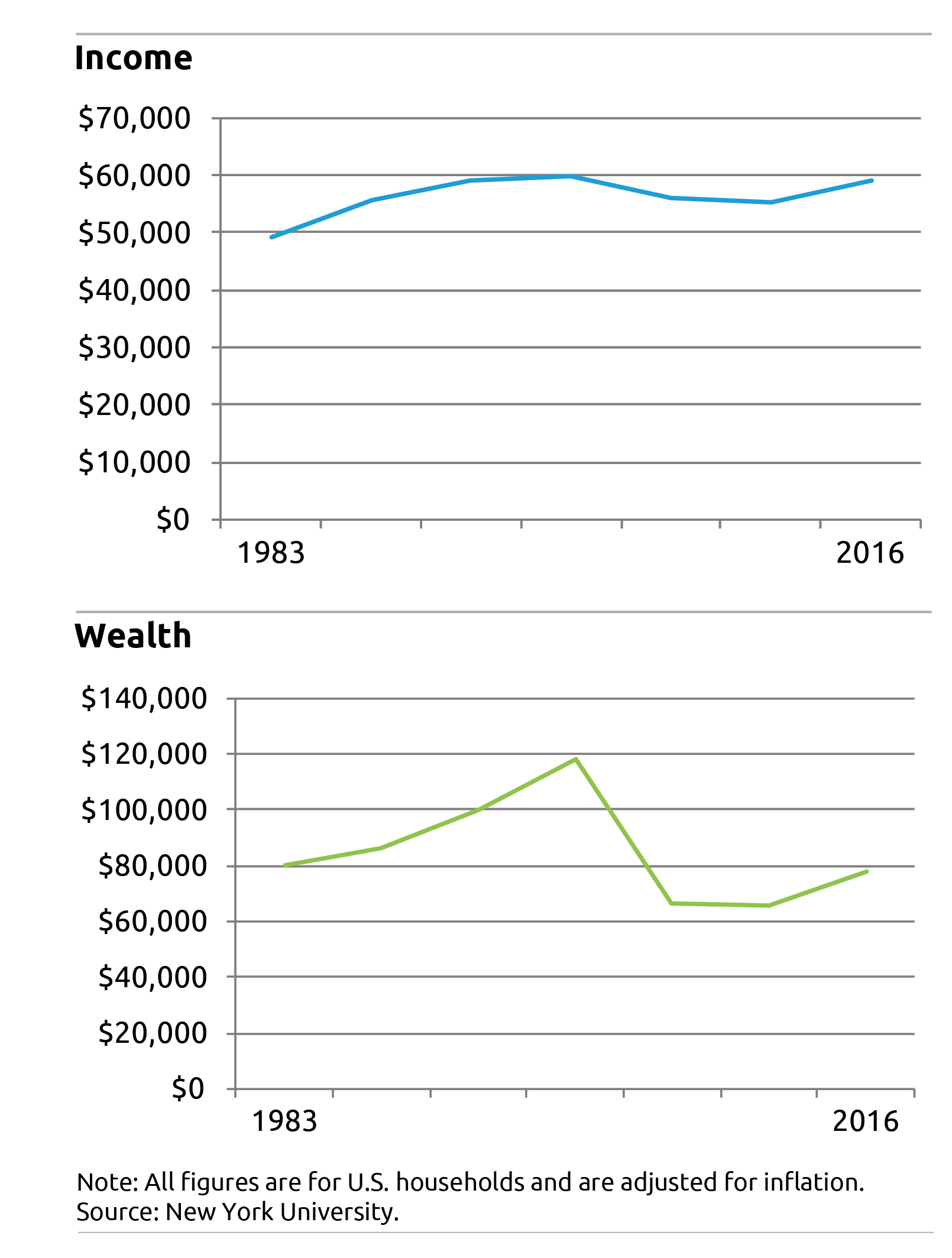

New York University economist Edward Wolff in a January report estimated that workers lost much ground in the 2008 recession and never recovered. The typical family’s net worth, adjusted for inflation, is no higher than it was in 1983 and far below the pre-recession peak. Granted, workers’ wages have gone up recently, though barely faster than inflation, but they had been flat for 15 years. Workers are also funding more of their retirement and health insurance.

Wartzman’s theme in “The End of Loyalty: the Rise and Fall of Good Jobs in America” is that the system no longer works for regular people, because companies have weakened or broken the social contract they once had with their workers.

The loss of employer loyalty is one way to look at the state of labor today. The loss of workers’ leverage against global corporations is another. …Learn More

August 23, 2018

Maybe You Can Slow Cognitive Decline

After decades of study devoted to describing the negative effects of dementia, a new generation of researchers is pursuing a more encouraging line of inquiry: finding ways that seniors can slow the inevitable decline.

One vein of this research, still in its infancy, considers whether seniors could reduce the risk of dementia if they engage in volunteer work. Several studies focus on volunteering, because most of the population with the greatest risk of dementia – people over age 65 – is no longer working.

There’s no suggestion that volunteering can prevent dementia. However, one new study, by Swedish and European researchers, found that Swedes between 65 and 69 who volunteer had a “significant decrease in cognitive complaints,” compared with the non-volunteers. The seniors answered a survey questionnaire at the beginning and end of the 5-year study that gauged whether they had experienced any changes in each of four complaints: “problems concentrating,” “difficulty making decisions,” “difficulty remembering,” and “difficulty thinking clearly.”

The study didn’t go so far as to claim that volunteering actually caused the improvements either. But it highlighted how volunteering might reduce the symptoms, possibly because it keeps older people more physically and mentally fit.

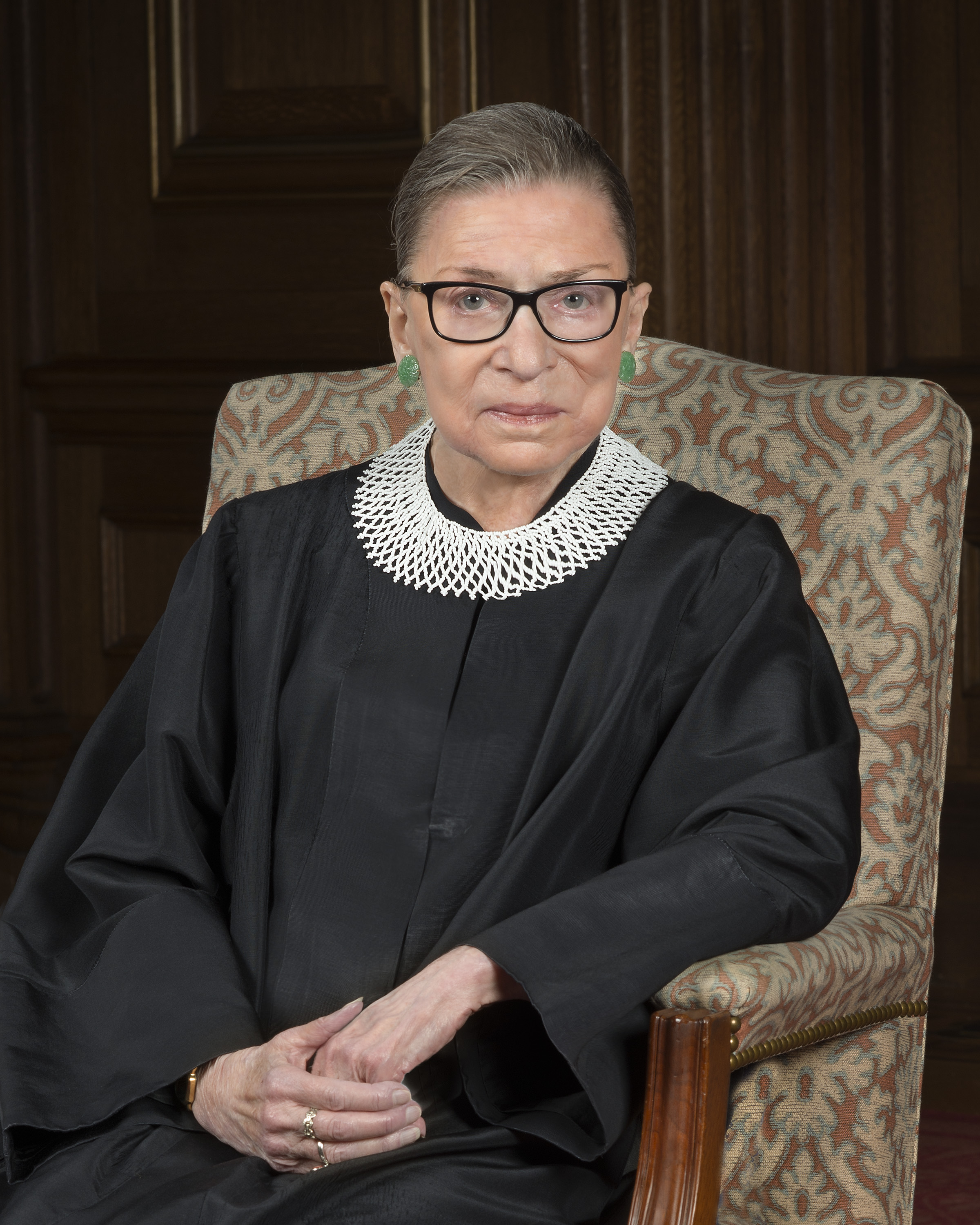

Indeed, the cognitive benefits of exercise have been understood for so long that they’ve become a perennial topic in the mainstream media. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 85, has become the poster child for elderly exercisers, with a personal trainer overseeing her push-ups and turns on an elliptical machine in a CNN Films documentary, “RBG.”

The research confirms that she’s doing what she needs to do to stay sharp for her beloved job: aerobic exercise in particular protects seniors’ brain matter from deterioration; weight training and stretching exercises do not.

A research team’s 2014 review of 73 prior studies on volunteer work found multiple benefits: “volunteering in later life is associated with significant psychosocial, physical, cognitive, and functional benefits for healthy older adults.” The paper, which appeared in the Psychological Bulletin of the American Psychological Association, defined psychosocial well-being as having greater life satisfaction, higher executive function, being happier and having a robust social network. …Learn More